The Negative Impact of the War on Drugs on Public Health: The Hidden Hepatitis C Epidemic

Drug War

Drug Decriminalization

Drug Policy Reform

Drug Prohibition

Drug War Articles

Harm Reduction

Hepatitis C Research Articles and News

Overview

Originally Published: 07/26/2014

Post Date: 07/26/2014

Source Publication: Click here

by THE GLOBAL COMMISSION ON DRUG POLICY

Attachment Files

PDF | The Negative Impact of the War on Drugs on Public Health: The Hidden Hepatitis C Epidemic

Summary/Abstract

The Global Commission on Drug Policy Report on The Negative Impact of the War on Drugs on Public Health: The Hidden Hepatitis C Epidemic.

Content

Hepatitis C is a highly prevalent chronic viral infection which poses major public health, economic and social crises, particularly in low and middle income countries. The global hepatitis C epidemic has been described by the World Health Organization as a ‘viral time bomb’, yet continues to receive little attention. Access to preventative services is far too low, while diagnosis and treatment are prohibitively expensive and remain inaccessible for most people in need. Public awareness and political will with regard to hepatitis C are also too low, and national hepatitis surveillance is often non-existent.

The hepatitis C virus is highly infectious and is easily transmitted through blood-to-blood contact. It therefore disproportionately impacts upon people who inject drugs: of the 16 million people who inject drugs around the world, an estimated 10 million are living with hepatitis C. In some of the countries with the harshest drug policies, the majority of people who inject drugs are living with hepatitis C – more than 90 percent in places such as Thailand and parts of the Russian Federation.

The hepatitis C virus causes debilitating and fatal disease in around a quarter of those who are chronically infected, and is an increasing cause of premature death among people who inject drugs. Globally, most HIV-infected people who inject drugs are also living with a hepatitis C infection. Harm reduction services – such as the provision of sterile needles and syringes and opioid substitution therapy – can effectively prevent hepatitis C transmission among people who inject drugs, provided they are accessible and delivered at the required scale.

Instead of investing in effective prevention and treatment programmes to achieve the required coverage, governments continue to waste billions of dollars each year on arresting and punishing drug users – a gross misallocation of limited resources that could be more efficiently used for public health and preventive approaches. At the same time, repressive drug policies have fuelled the stigmatisation, discrimination and mass incarceration of people who use drugs. As a result, there are very few countries that have reported significant declines in new infections of hepatitis C among this population. This failure of governments to prevent and control hepatitis disease has great significance for future costs to health and welfare budgets in many countries.

In 2012 the Global Commission on Drug Policy released a report that outlined how the ‘war on drugs’ is driving the HIV epidemic among people who use drugs. The present report focuses on hepatitis C as it represents another massive and deadly epidemic for this population. It provides a brief overview of the hepatitis C virus, before exploring how the ‘war on drugs’ and repressive drug policies are failing to drive transmission down.

The silence about the harms of repressive drug policies has been broken – they are ineffective, violate basic human rights, generate violence, and expose individuals and communities to unnecessary risks. Hepatitis C is one of these harms – yet it is both preventable and curable when public health is the focus of the drug response. Now is the time to reform.

MAIN RECOMMENDATIONS

- Governments should publicly acknowledge the importance of the hepatitis C epidemic and its significant human, economic and social costs, particularly among people who use drugs.

- Governments must acknowledge that drug policy approaches dominated by strict law enforcement practices perpetuate the spread of hepatitis C (as well as HIV and other health harms). They do this by exacerbating the social marginalisation faced by people who use drugs, and by undermining their access to essential harm reduction and treatment services.

- Governments should therefore reform existing drug policies – ending the criminalisation and mass incarceration of people who use drugs, and the forced treatment of drug dependence.

- Governments must immediately redirect resources away from the ‘war on drugs’ and into public health approaches that maximise hepatitis C prevention and care, developed with the involvement of, the most affected communities.

- Drug policy effectiveness should be measured by indicators that have real meaning for affected communities, such as reduced rates of HIV and hepatitis transmission and mortality, increased service coverage and access, reduced drug market violence, reduced human rights violations, and reduced incarceration.

- Governments must remove any legal or de facto restrictions on the provision of sterile injection equipment and other harm reduction services, as well as opioid substitution therapy, in line with World Health Organisation guidance. It is critical that these services are delivered at the scale required to impact upon hepatitis C transmission – both in the community but also in prisons and other closed settings.

- Governments should ensure that people who use drugs are not excluded from treatment programmes, by establishing national hepatitis C strategies and action plans with the input of civil society, affected communities, and actors from across the HIV, public health, social policy, drug control and criminal justice sectors.

- Governments must improve the quality and availability of data on hepatitis C, strengthening surveillance systems and better evaluating prevention and control programmes. This will, in turn, help to raise political and public awareness of the epidemic.

- Governments should enhance their efforts to reduce the costs of new and existing hepatitis C medicines – including through negotiations with pharmaceutical companies to ensure greater treatment access for all those in need. Governments, international bodies and civil society organisations should seek to replicate the successful reduction in HIV treatment costs around the world, including the use of patent law flexibilities to make them more accessible.

- The Global Commission calls upon the United Nations to demonstrate the necessary leadership and commitment to promote better national responses and achieve the reforms listed above.

- Act urgently: The ‘war on drugs’ has failed, and significant public health harms can be averted if action is taken now.

There are an estimated 16 million people who inject drugs around the world,1 and around 10 million of them are affected by hepatitis C.2 This epidemic is growing rapidly in many regions of the world, driven by ineffective and repressive drug policies and posing major economic and social threats to countries. The hepatitis C virus is transmitted through blood-to-blood contact. It can be prevented among people who use drugs when proven harm reduction interventions (such as the provision of sterile needles and syringes) are delivered at the required scale. Hepatitis C is also curable, yet very few people are able to access treatment due to its prohibitive costs. For people who use drugs, access to prevention or treatment are further decreased by criminalisation, imprisonment and systematic discrimination – including reluctance from some health care providers to offer treatment.

Epidemiology

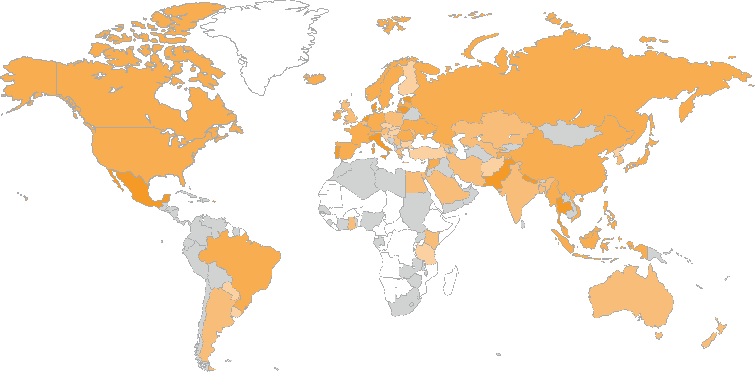

Hepatitis C is more than three times more prevalent among people who inject drugs than HIV.1,2 The largest numbers of hepatitis C infections among this population are reported in East and Southeast Asia (2.6 million people), and in Eastern Europe (2.3 million people). The three countries with the highest hepatitis C burden among people who inject drugs are China (1.6 million people), the Russian Federation (1.3 million people) and the USA (1.5 million people).2In most countries, more than half the people who inject drugs are living with hepatitis C.3,4 Infection rates are particularly high in many countries whose drug policies and law enforcement practices restrict access to sterile needles and syringes. In Thailand and parts of the Russian Federation, for example, up to 90 percent of people who inject drugs have tested positive for hepatitis C.5 The rate of new hepatitis C infections among people who inject drugs is often above 10 percent per year6 – but can be substantially higher in some countries: in a study from the USA, more than half of those who recently started injecting were infected.7

Crucially, the true size of this epidemic is likely underestimated as most countries have insufficient surveillance data.8,9 Increased efforts to build comprehensive, coordinated surveillance systems to monitor hepatitis infections are needed as a foundation for the scale-up of effective prevention and control services.10

|

FIGURE 1. (Above) THE PREVALENCE OF HEPATITIS C ANTIBODIES AMONG PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS2 Note: The prevalence data in this map provide cumulative information on infections over the last decades. High prevalence rates on this map therefore may not indicate high rates of new infections. Data on new hepatitis C infections (also known as ‘incidence’) is unavailable in most countries. |

RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE GLOBAL COMMISSION ON DRUG POLICY REPORT “WAR ON DRUGS”

- Break the taboo. Pursue an open debate and promote policies that effectively reduce consumption, and that prevent and reduce harms related to drug use and drug control policies. Increase investment in research and analysis into the impact of different policies and programs.

- Replace the criminalization and punishment of people who use drugs with the offer of health and treatment services to those who need them.

- Encourage experimentation by governments with models of legal regulation of drugs (with cannabis, for example) that are designed to undermine the power of organized crime and safeguard the health and security of their citizens.

- Establish better metrics, indicators and goals to measure progress.

- Challenge, rather than reinforce, common misconceptions about drug markets, drug use and drug dependence.

- Countries that continue to invest mostly in a law enforcement approach (despite the evidence) should focus their repressive actions on violent organized crime and drug traffickers, in order to reduce the harms associated with the illicit drug market.

- Promote alternative sentences for small-scale and first-time drug dealers.

- Invest more resources in evidence-based prevention, with a special focus on youth.

- Offer a wide and easily accessible range of options for treatment and care for drug dependence, including substitution and heroin-assisted treatment, with special attention to those most at risk, including those in prisons and other custodial settings.

- The United Nations system must provide leadership in the reform of global drug policy. This means promoting an effective approach based on evidence, supporting countries to develop drug policies that suit their context and meet their needs, and ensuring coherence among various UN agencies, policies and conventions.

- Act urgently: The war on drugs has failed, and policies need to change now.

See Attached PDF to view entire report